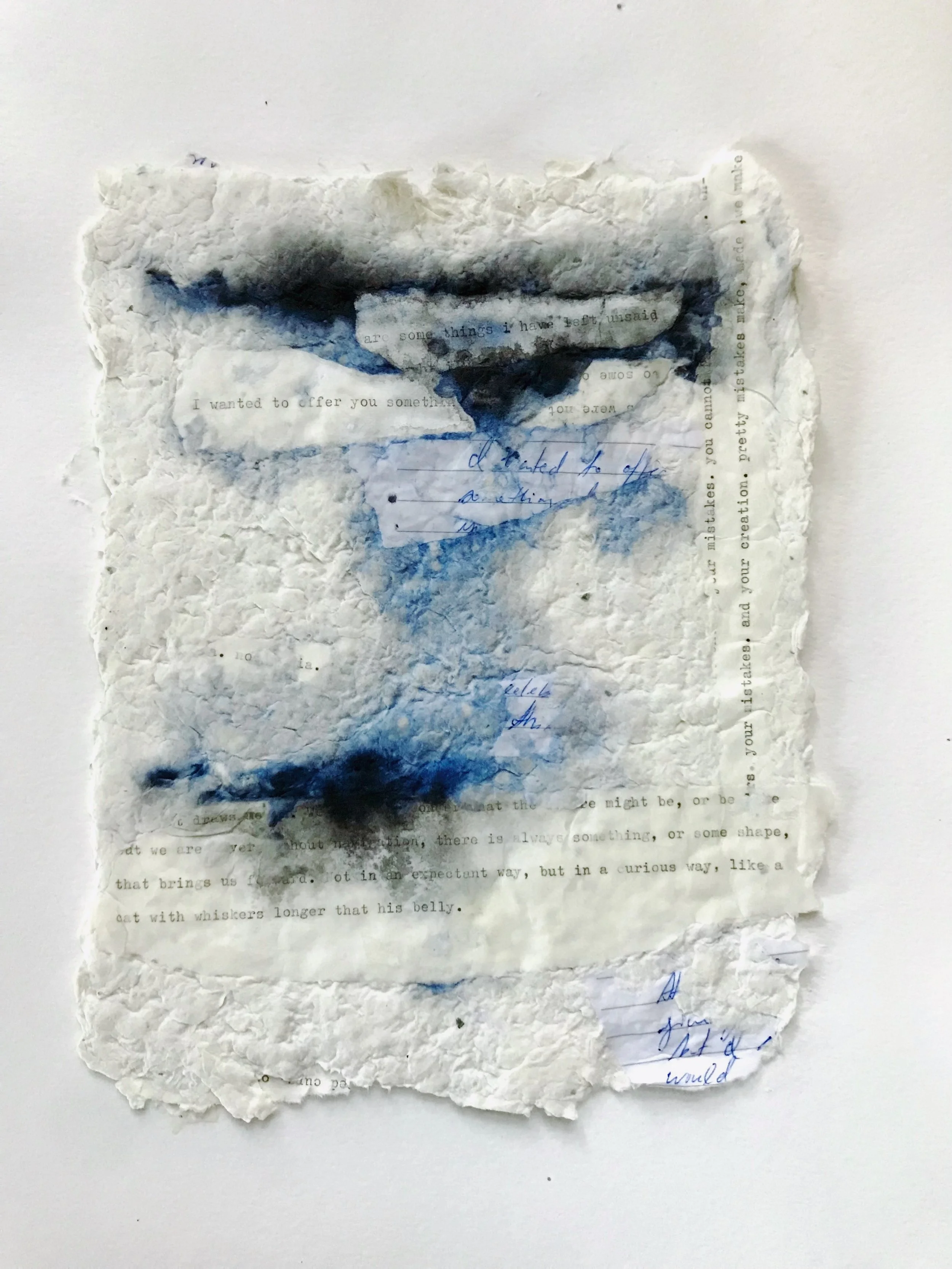

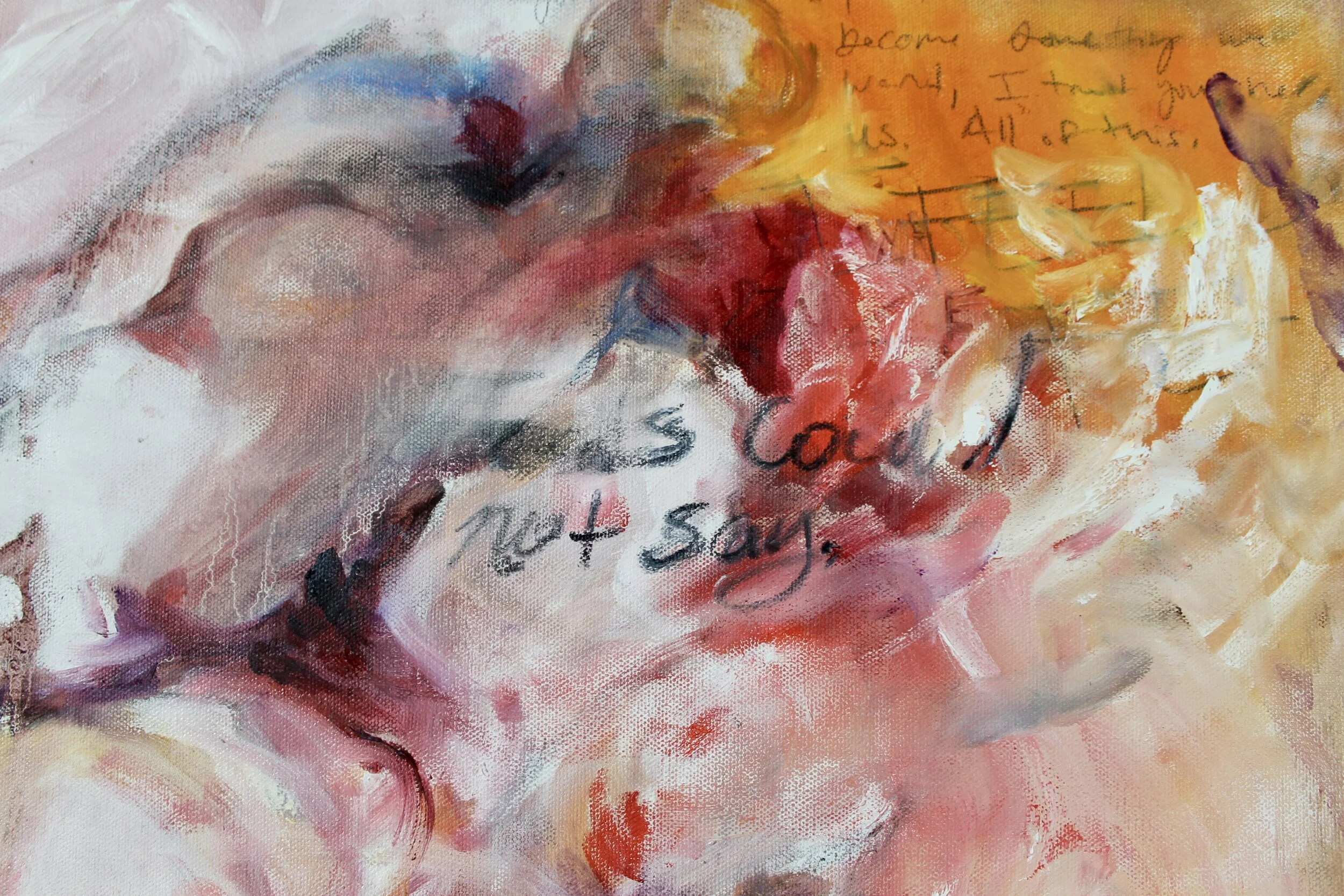

This pieces invites the viewer to experience an enumeration and a mark making that embodies harm, intimacy, purity, and the possibility of transformation.

When confronted with jarring truths it becomes easy to find them unimaginable. When we find something true unimaginable, we steal some of its actuality. The Fruits of Our Labor is at once a remembering, honoring, and enumerating of the harm of sexual violence. It is estimated that 73 seconds a person in the United States is sexually assaulted. Over 1150 people per day. Over 433,000 per year [RAINN, https://www.rainn.org/statistics/victims-sexual-violence]. It is likely that these estimations fall short.

This piece consists of 300 hundred cherries. 300 hundred people. 365 minutes.

In one sense The Fruits of Our Labor enumerates some of this harm but in another it invites the viewer and the performer into an act of reckoning.

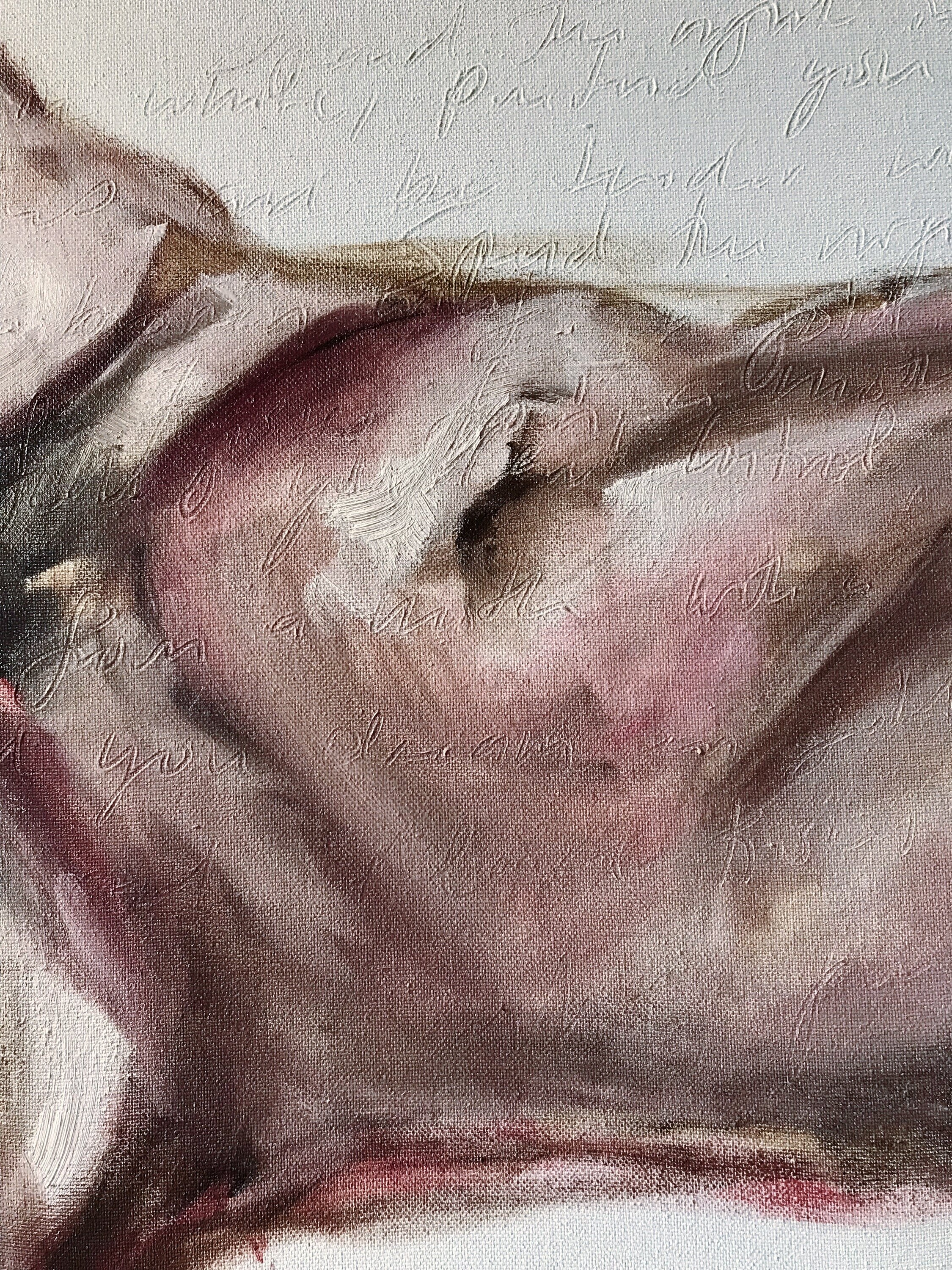

There is still a prevalent misconception that sexual assault is something that happens in a dark alley by a nameless, faceless enemy. The bed as a site of performance reminds us that most people experience sexual violence at the hands of someone they know, sometimes someone they trust, sometimes someone they love. The bed as the grounds for this commemoration is an active disruption to the sense of safety and comfort such a place normally evokes, for viewer and for performer.

The Fruits of Our Labor plays with a tension between numerical facts and experience. The contrast between the sterile environment, the white sheets and gown, the specified number of cherries and the disorganized pitting, and the staining disturbs the ways we often participate in activism. Even remarkable statistical observations often fail to impart something alive. The Fruits of Our Labor puts pressure on a statistic to impart more meaning to the viewer, to disturb them, to invite them into empathy, to consider the implications of that statistic beyond its numerical jarring-ness. It also asks the viewer and the performer to recognize each individual as meaningful, not merely part of a statistic, and to notice that collectively the impact is an irreparable change to a group and to an environment; all of the fruit, the staining on the bed, the staining of the performer. There is individual harm that matters and there is environmental harm that matters. Numbers cannot do this justice.

The artifacts remaining from this performance (the stained sheets, the conserved cherry stones, the ruined gown) are both individual and collective testimony.

Cherry as a central medium pays subversive homage to traditions of art history. Classically, depictions of fruit were rendered to convey youth, fertility, abundance. We are taught that paintings of ripe fruit are meant to convey something ephemeral and transient about life or ‘a moment’ in it. Occasionally there are depictions of decaying fruit which, we are taught, say something about the inevitability of death. This, to me, seems like a sort of odd and binary take on the conditions of being alive. You can be alive and not be alive sometimes. There are times when your life as you know it is taken from you and you are still breathing. There are times when you are taken from you. This piece seeks to play with an undocumented in-between of forceful decay and attempted revitalization.

Cherry stones are typically thrown away, useless, after the fruit has been eaten, but The Fruits of Our Labor comes to a close when the performer remembers the cherry stones. Conserving the stones is not only a remembrance and an acknowledgement of something real that happened, it is an act that centers the potential regrowth after sexual violence. This is not an optimistic message. We will not be the same, a cherry stone will never be a cherry again, but new roots can set in new soil, nutrients can be acquired in new ways, we can reattach to the ground and to the world around us. This is a necessary message. We cannot forget the harm that is happening every day. We cannot close our selves away, in belief or in heart, from the experiences of people who have been subject to sexual violence. We must remember the stones.

Thank you to Zoë Josephina Moon for her helpful thoughts during the making of this piece and for her emotional support.